Recap of our Disarming Hate Series

What we asked, what we answered, and what we promised each other

This past spring, ICNY’s hosted its very first three-part “Disarming Hate” series, which aimed to equip diverse faith and community leaders with an opportunity to discuss what we have identified as three main pillars of public safety: 1) understanding the root causes of violence, 2) prevention and intervention strategies, and 3) restorative justice.

The “Disarming Hate” series follows ICNY’s history of anti-gun violence and public safety advocacy and programming, most prominently through our 2021 Rabbi Marshall Meyer Retreat, “New York Faith Communities Respond to Gun Violence.” Although NYC has seen a decrease in gun-related crimes since the pandemic, we recognize a growing and alarming trend in hate-crimes and biases — a critical component we must continually address in our programming. There is a demonstrated need to respond to various forms of hatred and bias embodied in xenophobia, stereotypes, and prejudice. And more so, faith leaders are often the first stop for intimate issues among the community, making them uniquely positioned to interrupt cycles of harm and violence.

Read more about our sessions below!

Part I: Roots of Violence

In part I, “Roots of Violence,” we invited Rana Abdelhamid, Executive Director and Founder of Malikah, and Danielle Williams, Community Educator for CONNECT Faith, to discuss the current landscape of violence in NYC and how we speak about crime and harm.

Describe the current landscape of your work. What trends have you noticed regarding hate crimes and biases, especially around migrant communities? Where do these xenophobic sentiments stem from?

Which communities are particularly vulnerable, and what are the best ways to serve them?

In introducing her work around domestic violence (DV) at CONNECT Faith, Williams shares that DV and intimate partner violence (IPV), among other forms of violence, are ultimately have having power and control over another. They are issues rooted in sexism, racism, and a culture that has normalized permissive violence — ultimately making DV and IPV a social issue requiring collective action. This is especially relevant in thinking about our newest migrant and asylum-seeking neighbors who, as Williams explains, are living with layers of trauma from the political unrest and oppression they are escaping. Without adequate and collective acknowledgement of these layers, we see an alarming increase in xenophobic and nativist1 attitudes across our city, only perpetuating further harm.

Abdelhamid shares her personal story of being targeted and attacked as a young hijabi —a Muslim woman who covers her hair—in NYC. As a way of healing from this traumatizing experience, she began drawing upon her training in karate to teach her friends and community how to defend themselves. This ultimately led to the establishment of Malikah, an anti-violence and woman empowerment grassroots organization, where Abdelhamid has expanded her offerings to the community. The Muslim community, she explains, has been subjected to state-sanctioned violence and surveillance since 9/11 — a public rather than intimate form of violence. Public forms of violence may also include harassment on the streets, discrimination in housing and employment applications, and lack of government funding. Noticing these trends across the years, Abdelhamid asserts that our communities keep us safe, and curating vessels of safety where members can develop their leadership skills and voice is all the more critical.

What is “crime” and what drives people to commit harm/violence? What are different forms of violence (emotional, sexual, spiritual, etc.)?

Williams explains that “crime” is primarily a legal term and does not fully encompass the layers of harm that are actually present (e.g., financial abuse, emotional abuse, verbal abuse, etc.). She also highlighted that violence is not limited to individual relationships; rather, groups, entities, corporations, and political bodies can be both recipients and perpetrators of violence. Furthermore, the attitudes that exist at a systemic level, such as shaming and gaslighting, exacerbate and fuel the harm that occurs on an interpersonal level.

Building off Williams’ answer, Abdelhamid names that some of the most violent actors in global history are state actors; militarization of borders, war, and overpricing are just a few examples. These institutions are incredibly important to underline, as more often than not, the pathways to accountability are unclear or nonexistent. Thus, when Abdelhamid is curating spaces of safety and belonging at a grassroots level, she emphasizes restorative justice and healing, in contrast to the punitive and carceral approaches that have proven time and again to be ineffective.

Suggested next steps:

Throughout the session, both panelists named that certain state actors and institutions can be violent actors and create a culture that enhances interpersonal harm. Williams even powerfully stated, “the budget is a crime.” The New York City Council budget must be reflective of the community’s needs, ideally one that funds prosperity and peace. According to Williams, investing in our communities instead of punitive systems demonstrates that our people are not disposable; the relationships we build with one another are worthy of our collective time, resources, and commitment. One way to commit oneself and community to this process is by getting involved and submitting testimony throughout the budget cycle, which you can learn more about here.

Finally, both speakers affirm the efficacy of restorative justice approaches. Williams encourages participants to look inside one’s own tradition and research what is says of “justice” and “transformation.” More likely than not, the resources to practice restorative justice are already there.

Part II: Prevention and Intervention

In Part II of Disarming Hate, “Prevention and Intervention,” we invited William Evans from the Institute for Transformative Mentoring, Nova Felder from Bridging Africa and Black America - BABA, and Apostle Dr. Staci Ramos from the Garden of Gethsemane Ministries to discuss the various strategies they use to cultivate a culture of anti-violence and transformation in their communities.

Please introduce your respective organization, experience, and strategies for interrupting harm and building stronger communities.

To kick us off, Evans shared his personal upbringing in the South Bronx, having been a survivor of gun violence and wrongful arrest. Compounded other experiences, he recognized the feelings of anger and spite building up; but thankfully, with the support of his community and family members, he finished school, attended college, and founded “Neighborhood Ventures,” an organization that identifies mentors who can teach others how to identify trauma, triggers, and healing practices. More recently, he joined the Institute for Transformative Mentoring (ITM), whose signature 1500 course teaches transformative strategies and now offers fellows to develop public safety policies. Upon reflecting on his work, Evans emphasizes that there are ways communities are supporting and healing together that is often not documented as evidence-based practices, but needs to going forward.

Apostle Ramos shared her numerous affiliations include the Garden of Gethsemane and Harlem Clergy Community United and Beyond, the latter of which is a task force for street ministry. In Ramos’ work, she regularly meets and mentors young people, schools, and organizations on the ground, while also providing rapid-responses to local shootings and cases of violence. Like Evans, she emphasizes the need to document both the diversity and efficacy of strategies on-the-ground, while building community alliances who representatives are reflective of the perspectives and needs in the neighborhoods they serve.

Lastly, Felder shares that he joined BABA around 2020 during the height of the pandemic and one of his first major projects was assisting the survivors of the Twin Parks Northwest Fire in January 2022. During this time, BABA distributed nearly $100,000 work of goods from the Department of Education and shared resources on fire prevention. More recently, the organization has been responding to the needs of the new migrant population by offering language services and connections to other resources. In terms of anti-violence programming and advocacy, they have developed a program called “Cancel Crime Culture,” which seeks to build mentorship and teach participants how to understand historical and current harms (e.g., slavery, racism, etc.). By identifying the threads of punitiveness, the program seeks to transform perspectives and approaches into ones that emphasize love and understanding.

You’ve all emphasized the need for the younger generation to be engaged in anti-hate and anti-violence work. What does it mean to engage youth? How does that tangibly show up on strategies and the programming you all implement?

A critical component of being able to mentor and be in community with a younger generation requires leaders to work on themselves so they may return and serve their neighborhoods without passing on generational trauma, Evans explains. On retreats with youth, leaders and graduates of the Institute for Transformative Mentoring teach participants how to design a healing circle, one that features a mantle, talking piece, etc. Healing circles are one technique that teaches the younger generation how to process feelings of hurt and anger into ones of healing and restoration.

Apostle Ramos draws upon an organization called “Lead by Example,” which emerged from a prison ministry and was a leader in providing resources to inner-city youth. Drawing upon her experiences as a teacher and principal for inner-city schools, she emphasized the importance of being present and prepared to provide resources and alternatives that were not always available to former generations. One has to be ready to recognize any and all types of trauma, ranging from gun violence to hate crimes; more importantly, leaders should guide these individuals in processing how trauma lives and moves within ones psyche and body.

Felder emphasized that younger people need to see people that look like them in places of community leadership, so the relationships we build are more accessible and organic. Building off Apostle Ramos’ answer, he underlines that children experience punitive systems and violence everyday; for instance, walking through metal detectors at school is a form of violence that affects one’s upbringing and understanding of individual and collective safety. Felder reiterates that changing punitive approaches is critical through consistent self-reflection and -improvement (kaizen2) that incorporates historical and spiritual perspectives.

Suggested next steps:

During the Q&A, several topics emerged including the role of faith and preventing burnout. All the panelists agreed that while leaders play an inevitable role in building and sustaining community relationships, they must make time to “heal the healer.” Part of this commitment includes checking in with oneself on a daily basis and finding discernment.3 Be sure to create this space and cultivate the practice of self-improvement.

As a more actionable step, participants are encouraged to research and begin a relationship with their local anti-violence organization. Invite them into your space for a facilitated conversation on how your community can harness its collective power and implement one of the strategies discussed (e.g., mentorship program, educational program, walking ministry, etc.).

Part III: Restorative Justice

Building upon the threads of building deep and sustained community relationships across our first two sessions, we invited Anooj Bhandari (Restorative Justice Initiative), Markie Bledsoe-Grant and Joan Pangilinan-Taylor (NYS Division of Human Rights - Hate and Bias Prevention Unit) to lead our participants in a healing circle at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

While restorative justice and healing circles have been mentioned throughout our programming, we have not properly introduced the practice or its history. To begin our event, ICNY Executive Director Rev. Dr. Chloe Breyer offered some insight into the organization’s history with restorative practices in reentry programs. Next, Racial Justice Advocacy Fellow Shanaz Deen offered an introduction into the “Disarming Hate” series and introduced the facilitators.

Bledsoe-Grant grounded participants in a breathing exercise and transitioned the group into a presentation co-led with Bhandari. Together, the two explained that restorative practices are a collection of indigenous practices intended to care, repair, and strengthen communal spirits. They are older than the histories of gun violence, prisons, and policing; instead, they use consent, storytelling, and accountability to not only rectify harm but build community relationships over time.

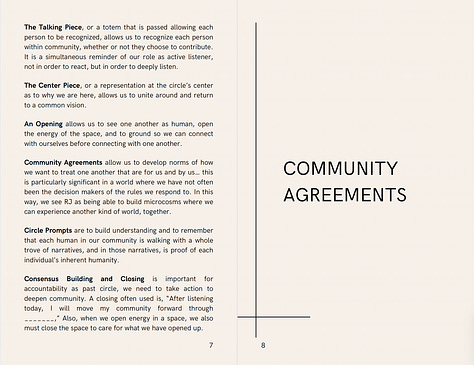

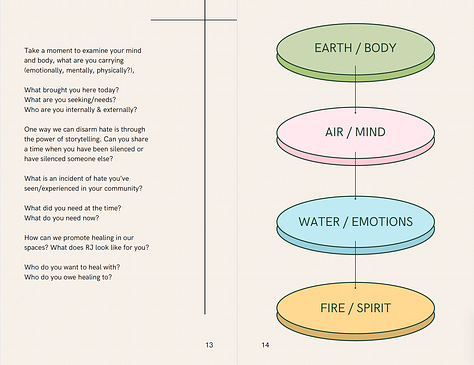

Next, we reviewed community agreements and guidelines, to which we added ideas, such as “step up, step back.” After, we explored the parts of a healing circle which include elements such as talking piece, center piece, opening, circle prompts, and closing. Finally, we split off into two circles to dive into the follow prompts:

What is a value that you hold as important to you? What does it mean to you and how does it show up in your life?

Where are the places in your community where you feel belonging? What happens there to build that sense?

As a (faith) leader, can you share a moment when you have created a space for others to belong? What did that look like?

Can you envision a NYC that responds to human need to belong? What does that look like?

To close the session, Ms. Sharonne Salaam, mother of Council member Dr. Yusef Salaam and founder of Justice 4 the Wrongfully Incarcerated offered her reflections of the event and the power of restorative justice in faith and activist communities.

Suggested next steps:

Learn more about restorative justice practices and find a facilitator around your neighborhood. Check out this background about the history of the restorative justice movement and this reading list from the Restorative Justice Initiative. Host a healing circle to build community and/or bring accountability to a harm committed.

Closing Reflections

The Interfaith Center of New York is incredibly grateful to those who participated and shared the “Disarming Hate” Series. The three segments were designed to encourage a thorough exploration around the harm and violence we all witness in our communities. All of our sessions emphasized the need to shift from punitive to restorative practices, which can only thrive in communities that know each other in deep and meaningful ways. We hope this experience was fruitful and inspire future initiatives. Please write to us here with your thoughts and ideas.

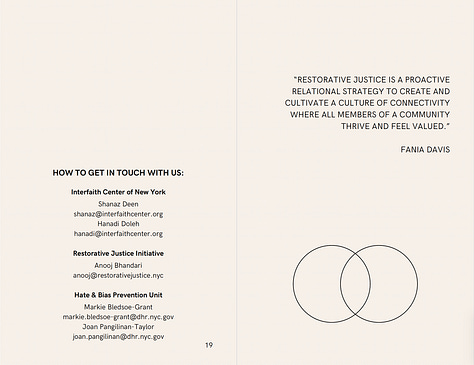

Reach Out to Our Facilitators

Rana Abdelhamid

Executive Director at Malikah

movement@malikah.org

Anooj Bhandari

Senior Coordinator of Training and Youth Programming at Restorative Justice Initiative

anooj@restorativejustice.nyc

Markie Bledsoe-Grant

Assistant Director at NYS Division of Human Rights - Hate and Bias Prevention Unit

Markie.Bledsoe-Grant@dhr.ny.gov

William Evans

Director at Institute for Transformative Mentoring

evanw934@newschool.edu

Nova Felder

Bridging Africa and Black America - BABA

nova.felder@gmail.com

Joan Pangilinan-Taylor

Senior Director at NYS Division of Human Rights - Hate and Bias Prevention Unit

Joan.Pangilinan-Taylor@dhr.ny.gov

Apostle Dr. Staci Ramos

Garden of Gethsemane Ministries

staciramos@yahoo.com

Danielle Williams

Community Educator at CONNECT

dwilliams@connectnyc.org

Nativism is the policy of protecting the interests of native-born or established inhabitants against those of immigrants.

The Japanese word kaizen means 'improvement' or 'change for better' (from 改 kai - change, revision; and 善 zen - virtue, goodness) with the inherent meaning of either 'continuous' or 'philosophy' in Japanese dictionaries and in everyday use.

Discernment can be defined in scientific (discerning what is true about the real world), normative (discerning value including what ought to be), and formal (deductive reasoning) contexts. The process of discernment, within judgment, involves going past the mere perception of something and making nuanced judgments about its properties or qualities.

Discernment in the Christian religion is considered a virtue, a discerning individual is considered to possess wisdom, and be of good judgement; especially so with regard to subject matter often overlooked by others.